Amleto Sommaruga and the battle of the Atlantic

The boat-Giuseppe Finzi, built by OTO in Livorno and commissioned in 1936, was one of the three ocean-going submarines of the Calvi class, among the largest submarines of the Regia Marina (84 meters long, they displaced 1,331 tons surfaced and 1,965 submerged; armed with two 120 mm guns, two machine guns and eight torpedo tubes). All three participated in the battle of the Atlantic from the summer of 1940, based in Bordeaux, France (where an Italian submarine base, called “Betasom”, had been created); after an initial deployment in the North Atlantic, they were much more successful as isolated raiders off the Caribbean and in the central and southern Atlantic, in 1942 and early 1943. They collectively sank 29 ships, totalling 161,118 GRT; more than half of these successes were achieved by Tazzoli alone, whereas Finzi was the least successful of the trio, sinking five ships for 30,760 GRT. I tell about her final fate at the end of the diary.

The man-Amleto Sommaruga was born in Milan, Lombardy

(Northern Italy) in 1920. In 1940, after Italy’s entry into World War II, he

was drafted for service in the Royal Italian Navy, along with his entire class

of the electrical engineering school in Milan. Due to his qualification in

electrical engineering, he became a sottocapo elettricista (Leading

Seaman/Electrician); he ended up being assigned to the submarine service, and

throughout the war he served on a total of six different submarines. Finzi was

his last sub, he served on it during two Atlantic missions, from October 1942

to April 1943. The end of his story, too, is told at the end of the diary.

And here is the diary…

“11 October 1942,

Monday

This morning I am

informed that I belong to the crew of the submarine Finzi. This means that I

will leave in about fifteen days for a three-month mission. I therefore pack up

my things and I move to the campgsite. Accommodation restricted to submariners,

and what an accomodation! For the first time since I have been in the Navy I

can sleep between two sheets in a cottage built for twenty people. The campsite

is composed of several similar cottages and is located in the middle of a wood,

where it is possible to find quiet and rest after many days of sacrifice onboard.

I go out and I find Janette, a blonde Parisian.

12 October 1942,

Tuesday

I board the “boat” for

the first time. Even though it’s in disorder, it seems to me that the interior

is practical and comfortable enough when compared to the “Mediterraneans” [the

smaller, 600-ton submarines that operated in the Mediterranean]. My mates seem

very kind and even the most senior part of the crew seem to be good people. I

spent the evening with Janette.

(…)

27 November 1942,

Tuesday This afternoon the posting for surface action stations were decided. I

received a rather risky task: resupplying the machine guns on the bridge. I did

not expect this, but I have to get used to every surprise.

(…)

29 October 1942,

Thursday

This morning, around

ten o’clock, all lined up on deck on the submarine, we were reviewed by his

excellency Alfieri [Dino Alfieri, Italian ambassador in Berlin] and staff

officers of the German Navy and Army. Finzi, the first boat scheduled to sail,

was thoroughly filmed, visited and congratulated by these staff officers. The

rest of the day had nothing of note.

(…)

1 November 1942,

Sunday

This morning the new

commander, Amendolia, introduced himself to the crew and with a laconic speech

showed himself a firm man, to whom one can entrust his life with faith. Good

skating in the afternoon.

(…)

6 Novemer 1942,

Friday; 7 November 1942, Saturday

We are ready to sail.

8 November 1942,

Sunday

I am in a bad way. My

face is all patched up due to a terrible tumble. Nevertheless, I did not

hesitate to go out with the entire crew to celebrate the last evening of shore

leave. An evening that ended with an air raid alarm and an exemplary ferocious

brawl with a group of German seamen.

9 November 1942,

Monday

We leave the campsite

to board the submarine. In the afternoon an order suspends our departure. It

seems that the channel has been mined by the English.

(…)

14 November 1942,

Saturday

We cast off the lines.

We exit from the sluice gates after being saluted by the honor guard detail of

the San Marco [Battalion] and by a crowd (not too large) of officers and

seamen. We enter the river, bound for the Atlantic. It is the first time that I

sail an ocean, in a wartime mission on a big submarine. I won’t hide that I

feel a certain pride in being among a crew that proud and serene sails for a

mission of a hundred days to bring to victory the banner of the distant

Fatherland. The day is very cold, a strong Tramontane wind makes navigation in

the channel a little difficult. 18:00: we reach Le Verdon, where we stop

waiting for daylight in order to leave the dangerous area and reach La Pallice.

Air raid alarm, as machine gunner I spend one and a half hour in the bridge,

where a freezing wind blows, without sighting anything. 24:00: I end my watch

at the electric engines. Tomorrow must be a terrible day.

15 November 1942,

Sunday

We sailed from Le

Verdon this morning at 9:15. We proceed with a rough sea, escorted by a German

cruiser. After four hours of sailing we meet the submarine Tazzoli, which is

coming back with an engine breakdown. We sight several mines on our route. We

sail in an area that has been mined by the English, therefore all the crew is

on deck with lifejackets on. At 18:00 we enter the harbour of La Pallice. Air

raid alarm and nothing else.

16 November 1942,

Monday

We’ve remained moored

in harbour for the entire day. I thus had the occasion to visit the impressive

German armored docks. We did an exchange of visits with the German submarines.

The usual air raid alarm.

(…)

18 November 1942,

Wednesda

We left, around 11

this morning, for exercises. A few miles from the harbour we had dived to 10

meters, when we suddenly heard a sharp blast to the left of the hull. We

realized we were being attacked by aircraft. We surfaced, as the riverbed was

too shallow to seek refuge underwater, and we prepared for defense, but the

aircraft (about fifteen) after dropping a few bombs around us, proceeded and

bombed La Pallice, killing 80 people. We returned unscathed at 16:00.

(…)

25 November 1942,

Wednesday

It is moored next to

us a German submarine that four days ago sank the biggest liner in the world,

the Queen Elizabeth of 85,000 tons [evidently a wrong claim/rumor]. I am in a

bad way because of an abscess that is growing on my knee. It wouldn’t be

anything if we were to remain in port, but it seems that tomorrow evening we

will sail for good, so with the fever and pain it causes it puts me off facing

the sea of Gascony.

26 November 1942,

Thursday

At 10:15 we sail from

La Pallice and we finally enter the Ocean, bound for… (we will know tomorrow

morning, when the commanding officer will open the secret envelope which

indicates the course). A fair crowd of Germans bids us goodbye from the quay,

wishing us a good patrol. These spontaneous displays fill us with enthusiasm

and pride in seeing that everyone admires our beautiful boat that perfectly

sails towards the high seas, with the flag proudly flying over the bridge.

[It’s a] pity that I have to stay in my bunk, in a bad way and with fever. At

17:25 a mine exploded some dozens meters from the hull. At 17:48 another mine

explosion, but this time closer. We come out unscathed from these damned

minefields.

(…)

28 November 1942, Saturday

Like yesterday, we submerge in the morning and resurface

in the evening. During the night we round Cape Finisterre, a point on the

north-western coast of Spain. With somewhat devious systems, as is common on

warships, the crew has learned the course that we are to follow in these three

months of patrol: North Africa, Cape Verde Islands, coast of Brazil, coast of

Argentina, the return has not been decided yet. The knee is getting better.

(…)

1 December 1942, Tuesday

During the night, the sea became quite rough, to the point

that around 10:00 we had to submerge. We resurface around 19:00 to recharge the

batteries, but the sea is still extremely stormy. I feel sick, I vomit but I

see that many are worse off than me. And yet, even in this condition, one has

to carry out his watch duty among the stifling heat and the oil smell of the

engines and the disgusting stench that comes from the stern. In which stern one

is supposed to sleep! And all of this will last for 90 days. We have been

sailing for seven days and we are all dirty, we feel the need of some water to

wash at least our face, but nothing, we are doomed to stay like this for the

entire duration of the patrol. The light, the fresh and brisk air, how much we

long for it; I never appreciated so much the light of the sun, the moonlight;

it’s seven days that I haven’t been seeing neither sunlight nor moonlight.

3 December 1942, Thursday

During the night, the sea became stormy again. Early in

the morning we sighted a 5,000-ton steamer and after a chase that lasted some

hours we found out that she was Portuguese. Thus we lost a treat… During the

night, the sea state worsened a lot.

4 December 1942, Friday, Saint Barbara [which in

Italy is the patron saint, among several other things, of the Navy]

The sea is still rough, we are sailing on the surface, far

off Gibraltar. At 12:25 (our time) we sight a big tanker, steaming north. Crash

dive, with a skillful manoeuvre we close in on her and we are about to fire

[the torpedoes], when we realize that she is Spanish. And this is the second

fiasco that befalls us…

(…)

6 December 1942, Sunday

During the night a serious mishap happened that, it seems,

will jeopardize the mission. Two of the four pumps of the engines broke down.

We therefore try with difficulty to put them back in working order, otherwise

the Commander is inclined to return. So we spent all day submerged, working

with a 40 degree temperature; naked men squeezed between pipes, cylinders,

disassembling, reassembling, unconcerned about anything, pushing arms and heads

in such narrow openings, that one would think it would be impossible to come

out again. And all of this because everyone dreads the idea of returning to

base, after so many sacrifices, having overcome the biggest dangers. No! God

will help us. We’ve had so much bad luck so far, but I still have faith in some

good fortune and in the Commander, who seems to be the only of our officers

that has his head in place.

(…)

8 December 1942, Tuesday

In the early hours of the morning the Commander ordered to

send Betasom a telegram asking for spare parts (we are 4,000 miles=7,408 km from

the base) or an order for us to come back. The answer was to come back, with

two engines running (we only have one functioning, otherwise we would not have

made this request). Work on board continues incessantly (to write this diary, I

am stealing a few minutes from the few hours of rest).

9 December 1942, Wednesday

Work on board continues intensely and with good results,

so much that in the afternoon we chased a steamer, that turned out to be

Spanish. The usual misfortune.

10 December 1942, Thursday

We did our utmost, everyone did all he could for the

success of the mission. But at 8:00 this morning we set course to return to

base. We are all tired and disheartened, only the idea of a good success kept

our spirits and morale high. The sea is calm.

(…)

21 December 1942, Monday

This morning at 06:00 we rendez-voused with the escort

ship (a German auxiliary cruiser). We narrowly avoided hitting two mines with

the stern, the third one struck the escort, which listed and sank. We continued

till the channel. Around 14:00, in order to complete this ill-fated mission, we

run aground on a sandbank, so that after countless manoeuvres we are forced to

wait for next day’s tide.

22 December 1942, Tuesday

After freeing ourselves, we continue and we finally reach

the Base at 18:00. After thirty days I thus set foot on land and I breathe some

of that clean air.

23 December 1942, Wednesday

I report sick and I am hospitalized for angina or

something else.

(…)

25 December 1942, Friday (Christmas)

Christmas Mass. I take Communion; I have thus spent,

although hospitalized, the third, but best wartime Christmas. [Between

December 1942 and January 1943, Finzi underwent maintenance

and repair work. In early February 1943 she prepared to sail for another patrol

with a new commanding officer, Lieutenant Mario Rossetto.]

3 February 1943, Wednesday

Today we loaded the last things, [and we had] our last

shore leave, therefore the last contact with the frivolous, but also wonderful

world.

4 February 1943, Thursday

At 16:00 we cast off the lines. We sail for the patrol. I

left ashore, among my things, a letter, perhaps the last, for my mother and for

Anna. If I won’t come back, one will be proud of her son, and the other will

know how much I loved her. A fair crowd of mates, friends, waved us goodbye

from the quay, wishing us good luck, good hunt. The tricolor in foreign land

flies high from the periscope. Standing on the quay, the San Marco detail pays

military honors as the submarine slowly sails away, carried by the river

current, and runs towards the Ocean, against England, towards Victory and

perhaps towards death.

(…)

6 February 1943, Saturday

We weigh anchor and, escorted by a German ship, we cross

the dangerous Gulf and we reach La Pallice at 17:00.

(…)

8 February 1943, Monday

Nothing new. Air raid alarm. A terrible bender with the

German comrades (strange, them of all people).

(…)

10 February 1943, Wednesday

Drills onboard. Tomorrow, it seems, we will sail for good.

I am listening from the radio, in the wardroom, some wonderful Italian songs.

So much beauty in that music, so many memories! And tomorrow I will bid

farewell to the land for three months.

11 February 1943, Thursday

At 11:30 we finally bid farewell to the land. We sail with

a fair enthusiasm for the mission. The enthusiasm, it should be noted, is

raised by an almost certain 60-day leave that we will have upon return. We sail

with a slightly rough sea.

(…)

14 February 1943, Sunday

Crash dive at 3:00, the radio receiver reported an

aircraft heading towards us. We remain submerged… It seems that the aicraft

located us with its magnetic waves.

15 February 1943, Monday

05:00. We try to resurface, our batteries are out and the

air inside is becoming heavy (we’ve been below for about 36 hours). We start

the diesel engines, but immediately thereafter the crash dive order is given.

The aircraft is not leaving us (it was probably relieved by another one) but

waits for us to be forced to resurface; therefore by this evening, either it

will leave, or we’ll have to deal with it. We surface at 20:00. It seems that

the aircraft did not leave! We manage to recharge until at 23:45 we have to

crash dive again. It [the aircraft] seems determined not to give in.

16 February 1943, Tuesday

We put out our face around 03:00, but at 07:00 we submerge

again, and again more than fast. Luckily the recharge is now complete and we

can stay below for a long time. We’ll have to see whether he too will have the

patience to wait for us. We resurface in the evening and finally the aircraft

is gone. We proceed undisturbed on the surface, with rough sea.

17 February 1943, Wednesday

We resurface at 04:00. And for today (perhaps the last day

of submerged navigation) we resume living in these dirty, foul, putrid and

stinky bowels of steel. The newspapers publish some nice little articles about

our life for those who write and read it, comfortably sitting in an armchair,

dining with their families. But it is not enough for them to be brimming with

patriotism, for us young heroes of the sea. They should add what is truly real

and would not look so, what the war is and cost to us young men, still

unbearded. Weeks and weeks of renouncing life, without seeing the sun, the

land, the sky. Breathing nothing else than foul air, already deprived of that

oxigen that is necessary to our existence. Unable to give our faces, our hands,

that wonderful and healthy contact with fresh water. We have to use only a few

kilograms [of water] per day, in its place we loaded that deadly contraptions

that are supposed to bring progress and civilization to our enemies. And then

so many other things that I will tell if God lets me…

18 February 1943, Thursday

We sail all day on the surface. We are off Lisbon, but 500

miles from the coast. [When we submerge], due to an error in calculating the balance,

we sink to 140 meters!

19 February 1943, Friday

This morning, under the pretext of fixing up something, I did a quick visit to the bridge and saw the sky for the first time in eight days. Just for a few minutes. We sail all day on the surface, with a slight swell. Around 22:00 we meet a steamer, but it has its lights on, therefore neutral. (...)

2 March 1943, Tuesday

An aircraft in the area makes us crash dive repeatedly

during the night and forces us to stay below for ten hours. At midnight, again,

yet another crash dive.

(…)

7 March 1943, Sunday

We sail on the surface, the sea is calm enough. 18:00. We

cross the Equator and I thus find myself sailing for the first time in the

Southern Emisphere, enjoying the famous Equatorial sunsets and seeing the

famous Southern Cross. The celebration with the traditional baptism is brief,

but not devoid of originality. A communal toast and on towards the enemy.

(…)

12 March 1943, Friday

Today, after several flying visits to the bridge from time

to time, we start to go up on deck in considerably skimpy swimsuits, some

without any swimsuit at all. The sun is quite scorching, the water looks like a

broth and thus the deck is turned into a wandering beach at 2 knots of speed.

We aren’t going very far at this speed, but we’re not in a hurry. We are now a

short distance from the Tropic of Capricorn, about 600 miles from Angola

(Portuguese colony). We will meet the submarine Da Vinci on 18 March, between

Staint Helena Island and the coast of Angola (South Africa).

13 March 1943, Saturday

This morning we captured a shark! And not a small one,

which then ended up in our bellies. During the afternoon we shelled some boxes

we had thrown into the sea… some noise with our two 120mm [guns], just to pass

the time! What can we do when the English are nowhere to be seen?

(…)

15 March 1943, Monday The usual torrid heat of the tropical

areas. The thermometer shows 41 degrees and we still continue. We will refuel

Da Vinci in a few days, she’s been luckier than us, she has sunk a 23,000-ton

liner [this was RMS Empress of Canada, of 21,157 GRT].

(…)

18 March 1943, Thursday

During the day we sail normally near the 12th parallel

South. 21:00: we sight and attack a steamer. As I am on the bridge next to the

machine guns, I can see the attack unfold very well, although hindered by the

Moon’s glare. We slowly advance, thus approaching the enemy ship (whose size is

8,000 tons) which proceeds on her course without (apparently) noticing our

presence. We close to 600 meters, to the point that we can make out her

features. The Commander fires (our bow is pointed towards her side) but the

torpedo misses one meter astern; [the commander] fires the second one, the

torpedo is so well-aimed that I plug my ears and prepare to hear the formidable

explosion. But the skilled enemy commander manoeuvres so that the torpedo

mysteriously disappears. At the third: Fire! that does not hit the target,

either, the enemy responds with gunfire, but luckily we only hear the shells

hissing over our heads. We crash dive (why, I wonder… when we have two big

guns) and the steamer scrams away. We resurface shortly thereafter to chase

her, and we have almost reached her when our old engines break down and at this

same moment we sight the Da Vinci, which continues the attack.

19 March 1943, Friday

Da Vinci does not show up, she’s probably busy with the

ships we ‘left’ to her.

20 March 1943, Saturday

In the early hours of the morning we meet Da Vinci, just

back from the chase, ready to receive our oil and torpedoes. Wow! In the middle

of the Atlantic Ocean, to transfer torpedoes weighing two ton sto another

submarine, without being disturbed in the least. The refuelling continues till

late in the evening. We take a prisoner onboard, an English seaman, the only

survivor of the crew of the ship that escaped us and was sunk by Da Vinci. [Note:

this was the British steamer Lulworth Hill of 7,628 GRT, en

route from Mauritius to Liverpool with a cargo of sugar, fiber and rum. She had

a crew of thirty-nine, in reality there had been fifteen original survivors,

but Da Vinci had only taken prisoner one, Royal Navy gunner

James Leslie Hull, who was then transferred to Finzi – luckily

for him, as on her return trip Da Vinci was sunk with all

hands. The other fourteen survivors were left on their raft, they drifted for

fifty days before being found and rescued by the destroyer HMS Rapid:

by then, only two were still alive.] From an Italian officer

(transferred to us by Da Vinci), taken prisoner in Africa, we learned that he

was being carried with 500 compatriots and 4,500 passengers on the Express of

Canadian [Empress of Canada], bound for Senegal and sunk by Da Vinci.

[Note: Empress of Canada, used as a troopship and en route from

Durban to the UK via Takoradi, was carrying 1,346 people, including

Commonwealth servicemen, Greek and Polish refugees, and 499 Italian prisoners

of war. 392 people died, more than half of them being Italian prisoners. Empress

of Canada was the largest ship ever sunk by an Italian submarine, but

this was a very bitter victory for Da Vinci. The officer mentioned

by Sommaruga was Medical Second Lieutenant Vittorio Del Vecchio, picked up by Da

Vinci before leaving the scene.]

21 March 1943, Sunday

Course 310. We return to base, but it will take over a

month.

(…)

24 March 1943, Wednesday

We are always sailing on the surface, almost exactly

following the course of the outbound trip. A huge pack of dolphins has been

following us since yesterday, boldly playing with our bow. Every now and then I

spot a fast-flying swallow; it passes near the top of the periscopes, as if

greeting us, then it flows towards the land that we haven’t seen in almost two

months.

(…)

26 March 1943, Friday

The usual monotonous navigation, that could drive you mad.

Late in the afternoon a fair-sized whale (about 15 meters) merrily loiters

around our hull. With the intention to do us a pleasant thing.

27 March 1943, Saturday

We cross again the Equator.

28 March 1943, Sunday

16:05 hrs. We start an attack against a steamer that we

sighted on our course a few minutes ago. The torpedoing could hardly be

successful. With exemplary calm the Commander directs from the bridge the

change of course towards the ship that, unaware of her destiny, is sailing on

(a thousand meters from us). We fire a couple of torpedoes, one misses, the

other hits. Another couple is fired and both of the deadly weapons hit home.

Thus the ship, thrice hit, sinks in thirty seconds. We slowly proceed towards

the place of the sinking, and among the floating wreckage we can discern

several lights, red and green. They are the small lights placed on the

lifejackets. We hear screams of pain, calls for help, many, probably most of

them are surely badly wounded, terrified by the presence of many sharks that

voraciously rush on those wounded, almost finished bodies. With the searchlight

we spot a survivor hanging on a piece of wreckage, we approach in order to save

him, but when we are a few meters away (when we can aready discern his

features) he sinks, as caught by a whirpool, a shark or who knows what. We

manage to haul one aboard, who is a pitiful sight to everyone. On his face

turned white, with eyes almost out of the orbits, it is possible to see the

recent terror, the double fear he experienced causes him a nervous shock that

makes him continuously tremble from head to toe. Poor guy! He kneels before the

Commander and with folded hands he begs not to kill him, not to throw him to

the monsters that crawl in the sea. As if he has ended up in the hands of

savages! From his account (he is Portuguese) in a mixed language made up of

French, Spanish and English, we learn that the ship that we sank was loaded

with ore, her name was "Granitus" bound for Fretwoo [Freetown]. I

thus took part in the sinking of something belonging to the English enemy, but

at the same time I also took part, in a way, in the killing of some fifty

people. Because the war wants this! [Note: the ship’s actual name was "Granicos".

She was a Greek steamer of 3,689 GRT, en route from Rio de Janeiro to Loch Ewe,

via Freetown, with a cargo of quartz and iron ore. She had a crew of

thirty-four; thirty-two were killed, one survivor – the Portuguese sailor

Joaquim Rodriguez – was picked up by Finzi, the other one was not

noticed by the submarine and was rescued on 4 April, from a liferaft, by the

tanker Leighton.]

29 March 1943, Monday

15:55: We sight a large steamer 23:00: We continue the

pursuit of the ship, which is sailing south at a good speed. Under the cover of

darkness, we close in on the enemy ship…

30 March 1943, Tuesday

…which seems to have increased speed. From 2,600 meters, a couple of torpedoes are fired from our stern; immediately thereafter, another couple is fired; two dull roars and the ship is hit. 1:12: the ship sinks. After an agony of a dozen minutes, the English Navy [sic] auxiliary cruiser [note, actually the ship was not an auxiliary cruiser] disappears beneath the waves. Like we did the previous night, we approach the site of the sinking and we observe several lifeboats loaded with survivors. One of them, by order of the Commander, comes alongside us. We ask who wants to come aboard and be taken prisoner. Nobody speaks, all those sailors prefer remain at sea in a lifeboat rather than be taken by the enemy. Before leaving them to their fate, we ask them if they need anything; [they answer] nothing except cigarettes. We hand them several packs and since we need a prisoner, the first guy who grabs them is brough aboard. The others thank us warmly and leave. We have thus sunk our second steamer, but without causing many victims. We have three prisoners onboard. [Note: this was the British steamer Celtic Star of 5,575 GRT, en route from Greenock to Buenos Aires, via Manchester, Freetown and Montevideo, with 4,410 tons of general cargo and mail. She had a crew of sixty-six, two were killed in the sinking, one – the Canadian seaman George Pattinson, who was at his third sinking – was taken prisoner by Finzi, the other sixty-three were all rescued on the following day by the anti-submarine trawler HMS Wastwater.] (...)

6 April 1943, Tuesday

Today we were allowed [on deck] to breath some fresh air.

What a weird sight are our bodies offering: flaccid, oily, long beards,

disheveled hair, ripped clothing, without any trace of their original color.

The color and smell of oil, the fuel whose fumes, that intoxicates our lungs,

so long deprived of that pure oxygen that is so important for our existence, we

have been breathing for 55 days. In the evening we sight a steamer that from

its visible lights can be recognized as belonging to a neutral country. We

therefore let it go without disturbing it with our fearful presence.

(…)

12 April 1943, Monday

Around 8:00 an aircraft disturbed our voyage by forcing us

to submerge for a few hours. We suddenly hear the explosion of several depth

charges, luckily rather distant, which cause minimal damage. The hydrophones

report propeller noise from a destroyer that is sailing away. We resurface

around 10:30. We are off Lisbon.

(…)

15 April 1943, Thursday

Around 4:00 an aircraft disturbs us, so we go under again.

We resurface in the afternoon but we are forced to submerge.

16 April 1943, Friday

We sailed on the surface for a good part of the night,

thus bringing ourselves about 200 miles from the mouth of the Gironde. During

the day we tried to proceed [towards the base], but the aircraft forced us to

dive for six times.

17 April 1943, Saturday

We dive to about fifty meters after reporting our position

to the Base, arranging the rendez-vous with the German escort ship that should

accompany us till the mouth of the river. In the afternoon we hear distant bomb

explosions, then a destroyer approaching, signalled by the distinctive rustle

of their engines. We remain in total stillness, absolute silence (as I write, I

hear the distant explosions of depth charges). We surface in the late afternoon

and without being disturbed we recharge and then we dive again.

18 April 1943, Sunday

We are submerged, 25 miles from the spot where we will meet the escort. It’s one o’clock and heavy explosions (probably magnetic mines) that shake the entire hull have been following one another for half an hour. While writing these lines, I counted half a dozen explosions that were rather close. Someone, with the classic calm that one should never lose, gets out a prayer card. Another, his town’s patron saint. The cheerfulness of a moment ago disappeared from everyone’s face. The Base is about a hundred miles from here, but we know that right in this little stretch of sea, dozens and dozens of our comrades lay entombed forever in their steel coffins. This is supposed to be the last night at sea, but the hidden dangers that the enemy has strewn in this sea of Gascony, make it dangerous and particularly feared. It’s two o’clock and I try to lay down on my stinky mattress, perhaps, God willing, in a few hours we shall see the longed-for land. … 6:33: sighting of the escort ship. We hoist the national flag, the red pennants with the tonnage of the sunken ships, and everyone on deck. We sail with an escort of four ships positioned around us as if in a cross, in order to protect us from possible air strikes and from drifting mines. 8:15: the jagged strip of land with the lighthouse, which shows us the entrance of the channel, becomes visible on the horizon. We finally believe that we are back in contact with the world, with life; but all of a sudden, while we are all singing and showing our joy for the forthcoming arrival, we hear a formidable explosion, a crash, a sudden stop of the submarine. A huge water column immediately rises a few meters from the stern. A magnetic mine that owing to a rare and lucky chance, exploded very close to the hull [but] without having touched it. The ships rush towards us, while we are assessing the damage caused by the explosion. Poor “boat”, in the inside, especially in the stern, there’s a confusion beyond words, in the stern compartment everything is broken by a breach in the pressure hull; more than a little water is rushing in. But with this we saved ourselves by the skin of our teeth and soon the good humour comes back, we proceed, the land is so close. We stop at noon in Le Verdon, where we finally receive mail and we see the land on both sides. 16:00: after sailing for four hours in the channel (Gironde) we arrive in Bordeaux. On the quay, besides the honor detail from the San Marco Battalion, women, authorities, Staff of the Atlantic Base and a crowd of friends and sailors who enthusiastically wait for us. We throw the “lines on the dock”, a band plays the national anthenm, then an unanimous cheer to Finzi’s crew. Bunches of flowers are offered by the snow white hands of those pretty little women (such a difference with our skin, that did not have any contact with water in almost three months) and are placed among the pennants at the top of the periscopes. The Commanding Officer goes ashore. Then Commander Grossi [Captain Enzo Grossi, the last commanding officer of Betasom] praises and congratulates us.”

Final notes about the protagonist(s).

After this mission, following an agreement between Italy and

Germany (which needed transport submarines for its plan to exchange German

weapons technology for rare raw materials from Japanese-held territories), Finzi underwent

repair and transformation work which turned her into a transport submarine, for

transport missions between Europe and the Far East. Guns and attack periscopes

were removed, the torpedo tubes were cut, ammunition and torpedo depots were

turned into cargo holds, etc. This work was completed in July 1943, and by then Finzi was

the only survivor of the three boats of her class: Pietro Calvi,

the lead boat, had been sunk on 15 July 1942 by the sloop HMS Lulworth while

attacking a convoy; Enrico Tazzoli, having also been turned into a

transport boat before Finzi, had vanished in May 1943 after sailing

for the Far East, possibly mined in the Bay of Biscay, although the truth will

likely never be know. Finzi, instead, never sailed for the Far

East. In July 1943 the Allies had landed in Sicily, Mussolini had been deposed,

and Germany correctly deduced that Italy would soon try to make a separate

peace with the Allies, so the German authorities delayed with various excuses

the departure of the last Italian submarines in Bordeaux, hoping to capture

them in case of an Italian surrender. Which is precisely what happened: on 8

September 1943, when news came of the Armistice of Cassibile, Finzi and

another Italian submarine, Alpino Bagnolini, were still in

Bordeaux. Betasom commander Enzo Grossi, a pro-German officer, disregarded

orders from Supermarina (the high command of the Italian Navy) to scuttle the

submarines, and did not even mention them to his subordinates; instead, he

moved Finzi and Bagnolini to the German

U-Boat bunkers in Bordeaux, where the two submarines were placed under German

armed guard, while still flying the Italian flag and keeping their Italian

crews. A few days later, Grossi gathered the crews and the remaining Betasom

personnel and invited them to choose between continuing the war alongside

Germany, or become prisoners. The majority chose the first option, some out of

conviction, others for fear of German reprisals. After the establishment of the

Italian Social Republic, Finzi and Bagnolini flew

the flag of the new rump state till 14 October 1943, when following the

declaration of war on Germany by the Kingdom of Italy, the Germans replaced the

Italian crews with German personnel. The two submarines were then commissioned

into the Kriegsmarine, Finzi becoming UIT 21. Most

of the Betasom personnel who had joined the RSI became part of the “1st

Atlantic Naval Infantry Division”, whose personnel was attached to German

garrisons on the Atlantic coast of France (it is little known that the foreign

troops in the Wehrmacht that were involved in the battle of Normandy also

included a few thousands Italians), others were repatriated and joined the

Tenth MAS Flotilla or other units of the RSI armed forces.

Unlike UIT 22 (the former Bagnolini),

which sailed for the Far East in January 1944 (but never reached her

destination, being sunk with all hands by an air attack off South Africa in

March), UIT 21 never left France. Despite extensive

maintenance and repair work, the Germans eventually concluded that the old and

worn-out submarine was too unreliable – especially her engines – to endure a

long voyage to the Far East, and thus laid her up in April 1944. On 20 or 25

August 1944, just before the German retreat from Bordeaux, Kriegsmarine

demolition engineers mined and blew up the former Finzi in the

U-Boat pens in Bordeaux. The wreck was later scrapped. The violence of the

explosions had thrown some metal debris from the submarine in the roof of the

U-Boat bunker, where they remain lodged to this day.

This was, thus, the end of Finzi’s story. Amleto

Sommaruga, however, was no longer part of it. The mine explosion that had

damaged Finzi in April 1943 had caused him ear damage that

would eventually leave him almost deaf, and as a consequence of this he had

left the submarine. After the September 1943 armistice and the German

occupation of Italy, he sought refuge in neutral Switzerland, where he remained

till the end of the war, working as a farm hand. After the war he moved to

Canada; having spent part of his youth in France, and thus knowing French, he

settled in Quebec, where he spent the rest of his life. He passed away five

years ago, aged 94.

The end.

|

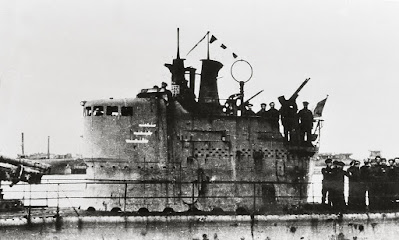

| Finzi returning from a patrol in 1942 (from www.naviearmatori.net/Giorgio Parodi) |

(the full diary can be found at www.betasom.it)

Commenti

Posta un commento