Giuseppe Anzevino and the battle of Cape Matapan

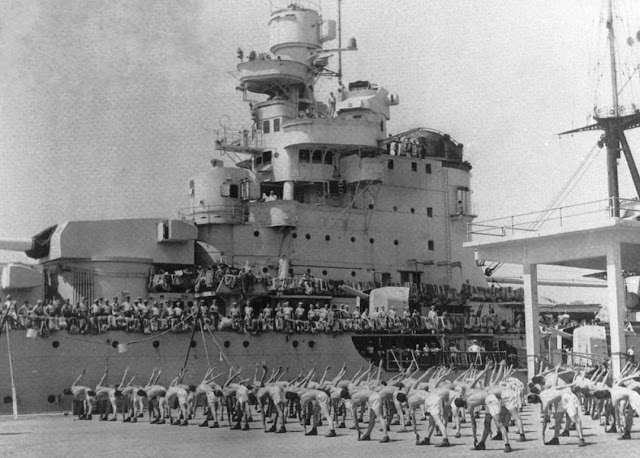

The heavy cruiser Pola was sunk in the battle of Cape Matapan, on 28 March 1941. Attacked by torpedo bombers, she was disabled by a torpedo hit in the engine rooms that left the ship dead in the water and powerless, unable to move her turrets and therefore use her guns; after the rest of her cruiser division, dispatched to her rescue, had been ambushed and destroyed by the battleships of the Mediterranean Fleet, the helpless Pola was boarded by the destroyer HMS Jervis, that took off the part of the crew that was still aboard, and was then finished off with torpedoes.

Seventeen-year-old gunner Giuseppe Anzevino, hailing from a village of Campania, was one of the 1,041 men aboard Pola on that night (from “La guerra dei radar. Il suicidio dell’Italia (1935-1943)” by Piero Baroni):

“After some days [mid-March 1941], we started to make a lot of preparations. We sailed. Nobody knew where we were going. But we were to join the [battleship] Vittorio Veneto. This was what I heard. We sailed for a couple of days. Then, action stations. It was a quiet, normal journey until, on 26 March, a bloody Sunderland aircraft appeared on the horizon… This aircraft was a sort of curse for us all. I was assigned as a lookout on the monkey bridge because I was a novice, they did not assign me to the guns, and from the bridge I heard the Executive Officer tell the Fire Control Officer “gift him with a couple of shells”… A couple of shells were fired. The plane seemed to have disappeared in the darkness, towards the distant horizon. Sunderlands were pretty big aircraft. We were a group of heavy cruisers with our destroyers and on 28 March we joined the great fleet where there was this gigantic battleship. White, beautiful, the Vittorio Veneto. It seemed as if the waves stepped aside to let her through. (…) Seas off Cape Matapan, late afternoon on 28 March. We were two groups of heavy cruises and we were sailing next to the Vittorio Veneto at a distance of about a mile, as if to protect her. Later I learned that the Vittorio Veneto was sailing at a slow speed because she had been hit by a torpedo. With this formation and this huge ship in the center and the cruisers around her and many destroyers in the distance, barely visible, it seemed as if we ruled the sea. Then in the afternoon, four or five p.m. (it was starting to get dark, days were short), there was an air alert. Torpedo bombers everywhere. We were sailing as usual. The only thing was the tremendous anti-aircraft fire from the various ships and I got the impression that some shots from the cruisers’ machine guns ended up on our destroyers. It was an impression. I never had any confirmation of this. I was a lookout on the Admiral’s bridge [note: Pola was built to be used as a command ship and had an “Admiral’s bridge” besides the “Captain’s bridge”; but during her last mission there was no Admiral aboard, Zara being the flagship]. All of a sudden I heard an explosion, but not very loud. A column of water rose from the port side and then nothing else. Sure, there were some dead aboard, very few I heard, but I could not leave my post, on the bridge. And, despite it looked like we were proceeding as usual, we slowly started to drift leeward and we remained behind while the fleet sailed away. We remained alone. Alone and the night was falling. I had remained at my post, up on the monkey bridge as a lookout. I heard the screams of the wounded and some orders being given, but I had to remain at my post. There were binoculars next to my post and I started to examine the horizon despite all what was happening below. I remember someone saying: “They will come and take us in tow”. And from my lookout post on the monkey bridge, I saw the ships in the distance. They were battleships, not Italian ones, just on the horizon. I could see them clearly from up there. I gave the alarm. I also remember an older man who told me: “What do you know about it? You’re just a boy, you’ve never seen anything”. Sadly those were triangle-shaped silhouettes, typical of the British Barham-class battleships. All hell broke loose. It was the cruiser Fiume, I think, that took the first hits. I saw seamen thrown fifty meters into the sky: I saw Zara, another heavy cruiser, pounded with shells. We aboard [Pola] were silent. We did not have electric power because the torpedo had hit between the engine room and the electrical center. The ship was in the dark. We could do nothing. And I remember that the commanding officer, his name was Manlio De Pisa, ordered the crew to muster, but he spoke with a megaphone because we were trying to light a boiler. The crew was composed of about 1,200 men, a normal crew for the heavy cruisers. [De Pisa] said these words: “We are in danger. Those who want to die as heroes, remain aboard. Those who want to see their families again can abandon the ship”. All hell broke loose. [De Pisa] said “Long live Italy. Long live the King”. Some cheered back. Then I came down from the monkey bridge. There was no more reason… Fiume and Zara blew up. A destroyer also blew up. I did not know where to go. Someone had thrown a raft off the starboard side of the ship, and it was illuminated by a “Sanpietro” [?], that famous keg. Hundreds of men were throwing themselves on this raft. Struggle for survival. The raft became full, sank, turned over, came back to the surface empty and more men again… I was unconscious. I remember that I did not have feelings, but I wanted to jump overboard. (…) I did not know how to swim. And I was leaning against the No. 2 turret in the bow, and unfortunately I was leaning near the megaphone [?] that connected to the ammunition magazine. I started to hear cries. “You up there… help us. We’re in water up to our knees”. I was frozen. What could I do? I did not have fear, but I could not move away from there. These people below were yelling, crying, praying. Then they started to swear. Curses that cannot be repeated. They somehow resembled the curses that you can find in the Bible: “Cursed seven times, seventy-seven times… nobody will help you…” They were cursing the progeny of those who in that moment could have freed them [and did not]. They were trapped in this ammunition magazine, and since the adjacent compartments were flooded, the watertight doors could not be opened anymore. So it was a horrible death for these people. I was leaning there. What am I to do? I asked myself. A guy from my course passed in front of me. A Tuscan, Ricci Carlo. Who will ever mention this name again? He said a few rough words, his reality. “Hey Beppe [diminutive for Giuseppe], tell my mother, who lives in Liberty Squadre 35 in Florence, tell her that I die like an idiot”. He threw away his lifejacket and jumped into the water. To me this gesture was, I don’t say normal, but a consequence of what was happening aboard. I noticed that somebody was breaking the bar open. There were people drinking and people plotting revenge against those who had reported them for reasons that, you know… onboard it sufficed to let your hair grow too long, or to be found with your shoes dirty, or a stain on your collar, for you to be reported. They were plotting these revenges that… many of these revenges were extinguished in the water. But I had to jump into the water. I tied to my waist the lifejacket that Ricci had left. I did not dare to put it on because I had been told that our lifejackets were dangerous because they broke your neck when you jumped into the water; there were these things in the front and in the back that gave you a blow below your chin that… you could die. And I told myself, to die at seventeen… it did not seem right to me. There was a rope, I tied it to a railing and I tried to lower myself. By then the ship had settled about two meters lower into the water, if not more. As I lowered myself into the water, I felt something like a hand that was sustaining me. It was a wave. And I let myself be carried by this wave. This is it, I’m going, I told to myself. I had jumped from the side where the torpedo had hit. Nobody jumped from that side. I wanted to avoid the danger of jumping on the raft that was amidships off the starboard side, where many people came up to the surface, after the raft had turned over, in a supine position. They came up dead. I, instead, found myself undisturbed there in the water. I looked back and I saw the silhouette of my ship. She looked intact. The British weren’t firing anymore. By then, Fiume and Zara and the destroyers Alfieri and Carducci had gone to the bottom. Maybe the British had not yet noticed us, I don’t know, anyway I looked back every now and then and I saw the ship farther and farther away, then I heard a cry.

I looked hard and I saw a raft. I threw myself against it. I was threatened and told to stay out [of the raft]. Now, rafts have that rope all around them, so I grabbed [it]. “Can I stay like this?” I asked. A guy who was holding his stomach, and was bent forward, told me “Hello paisan”. Paisan? And I recognized a Mario Cavuoto, ordinary seaman. His brother was a secondo capo [Italian Navy non-commissioned officer rank, equivalent to Petty Officer Second Class] on Pola. His NCO brother died onboard [Pola]. He [Mario] was on the raft, wounded, but by keeping that position, bent forwards, he did not feel too much pain. The raft was drifting, it was not manoeuvrable. The ship was so distant, I saw her turn turtle, I saw her keel, then she reared up, she almost came back up again, she raised her stern into the sky and I saw her sink. We remained in the water till eight or nine in the morning. A destroyer came near. It was British. I am not very sure about her name. I think it was the Greyhound… The British decided who could live, who could die. They had a net along the side of the ship. The ones who were in the raft were the first to go aboard [the destroyer]. Afterwards, this Mario Cavuoto also climbed up. He grabbed the net with his right hand, with his left hand he was holding his stomach. Then he took the hand off his stomach and he grabbed the net with the other hand as well. It was my turn to come up. I looked up, where they helped the prisoners. I saw an Englishman who was standing there with his foot sticking out to send down those who were badly wounded. And I saw the foot of this Englishman and Mario who was climbing up. But he did not make it: he fell into the water. The water was clear. The wound opened, his guts came out and tangled around his body, and I climbed up [the net]. I had studied some French and English at school… I was rather in a bad shape as I had taken several splinters. Two [splinters] were planted in my head and the blood had clotted and I thought: if that guy was ready there with his foot to throw down that friend [Cavuoto], now they’ll throw me down as well. And I said the first word that came to my mind, “Help”. Another Englishman shouted, “He’s a kid”. I did not have any trace of beard. They helped me. After all, it was a help for someone who had exhausted his forces. Even a little thing, a smile, meant life to me. And I must say, I received a cup of hot tea, too. Then they started to inquire about my age. They believed that I was the son of the captain. I remember well that they said “You are the son of the captain, you are fourteen years old”. I said no, I am twenty, because I wanted to show that there was a man in front of them… Boy things. I was so young… after taking my name and surname, I had my dog tag, they saw that I was born in July 1923. They put me together with other prisoners. There was a British seaman, he started to ask me questions, but for what I could reply, only school level English… One thing is spoken English, another the English used by a certain social class. I said something in answer, but to me this was a great help because there was no meal aboard, but I was given a piece of white bread, as white as milk, and it was the first time I saw it. From there, they brought us to Alexandria”.

Of Pola’s 1,041 crew, two hundred and fifty-eight men,

including Captain Manlio De Pisa, were taken off the crippled ship by the

destroyer HMS Jervis, before scuttling her with torpedoes. Four

hundred and forty-seven, including Giuseppe Anzevino, were plucked from the

water and from the rafts by British destroyers during the night and the morning

on March 29. Three hundred and thirty-six, including Carlo Ricci, Mario Cavuoto

and his brother Luigi Cavuoto, were killed or missing at sea.

Commenti

Posta un commento